“The Flying Bomb” from C.I.C. (Combat Information Center), U.S. Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, August 1944.

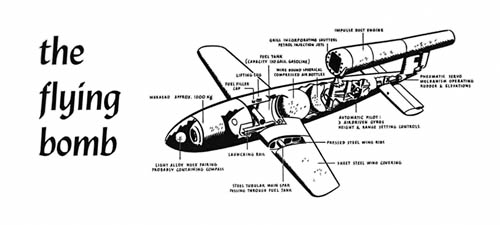

the flying bomb

The pilotless airborne bomb which was first used by the Germans on June 13, has been officially designated as the “Flying Bomb”. (Newspapers have referred to it also as “Doodle Bug” and as “Buzz Bomb”.)

This weapon, known to the Germans as V-1, appears to be one answer to Allied air supremacy in the Channel area. While the inaccuracy of the missiles as used to date is such as to make it impossible to assign specific military targets as objectives, approximately 35 percent of the bombs have landed in the London area causing considerable damage to non-military installations.

The bomb, as may be seen from the illustration, is of relatively simple construction and apparently designed for mass production.

From an examination of fragments and parts of unexploded bombs recovered in England, it has been possible to determine the method of operation. The bomb is originally launched from an inclined ramp on the mainland, by means not yet determined, at an initial speed of approximately 270 miles per hour and continues under the drive of the jet propulsion motor which operates as a result of the increased pressure developed on the forward side of the air intake grill by the high speed of the missile.

A clockwork mechanism which precesses the gyro normally under control of the magnetic compass allows the bomb to be put into a turn within three minutes after launching. The maximum duration of the turn is one minute and corresponds to about 40° in azimuth. After being put on course by this method, the missile flies in a straight line under control of the magnetic compass which precesses a gyro controlling a servo motor actuated by air pressure from two high pressure air bottles located in the fuselage. The gyro is further precessed by a barometric capsule which can be preset for any desired altitude up to 10,000 feet. A small two-bladed propeller, 10 centimeters long, mounted on a shaft geared to a veeder counter, registering to 9999, constitutes an air log. By pre-setting the counter, which is turned backwards during flight, the electrical fuse can be armed, the radio transmitter turned off, and the detonators in the tail assembly exploded. The radio transmitter, which appears in approximately one out of every twenty missiles, is provided in order that shore D/F stations may obtain fixes on the bomb for the purpose of correcting errors in flight. A prisoner of war has reported that the fix must be obtained and telephoned to the control central within ten seconds in order to insure sufficient accuracy. The detonators in the tail assembly operate at a pre-determined time prior to the end of the flight, shutting off the fuel supply and causing the elevators to operate and put the plane in a dive. At the same time, two small spoilers of different sizes are projected from the surfaces of the elevators presumably causing the plane to spin in.

Some instances have been reported in which the plane glided in to the target after the motor had stopped instead of diving. Later reports have indicated that some of the bombs circle before going into a dive. The exact reason for this is not known. but it is assumed that it is for the purpose of obtaining a fix as a check on the accuracy of the flight.

Countermeasures to date have consisted of:

a. Bombing launching sites.

b. Destruction of missiles by fighter planes.

c. Destruction of missiles by antiaircraft fire.

d. Use of barrage balloons.On one instance a fighter pilot who had run out of ammunition succeeded in crashing a bomb by tipping it over with his wing tips.

A summary of the results of the flying bomb attacks on England (as excerpted from Prime Minister Churchill’s address of July 6th) appears in “German Flying Bombs” in the July 12, 1944 issue of The O.N.I. Weekly.